This article was featured in One Great Story, New York’s reading recommendation newsletter. Sign up here to get it nightly.

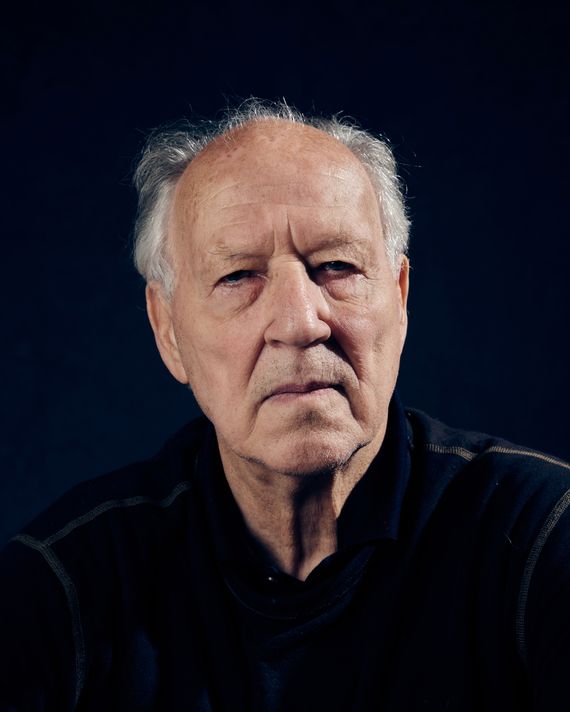

We find each other in the middle of nowhere, a very, very dubious location that stretches for a kilometer,” Werner Herzog tells me shortly after we meet near a parking lot on an overcast morning in Altadena, California. The filmmaker is a droll and enigmatic conversationalist, so when he says we’re like “explorers of the 19th century,” it’s not totally clear he’s joking. We are, in fact, far removed from the era of Arctic expeditions — outside the fence that borders NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, which controls America’s planetary rovers and space probes.

Early in his forthcoming memoir, Every Man for Himself and God Against All, Herzog describes breaking into this facility to get footage for a nascent film project. I thought we could discuss his gonzo mission near the perimeter he once scaled, but he has other ideas. “There’s an area at the top of the hill with picnic benches,” he suggests. Once we’re settled, he tells me, “I clomb the fence,” explaining that he prefers old terms like clomb (instead of climbed) from “the time of Wordsworth and Coleridge.” This is the only point in our interview when he musters more than a chuckle.

Twenty years ago, scientists were crashing the Galileo probe into Jupiter because it was out of fuel, and Herzog wanted to film them celebrating and mourning the 14-year mission. “Normally, I don’t get caught,” he says. “I bamboozle them out of their wits.” Herzog’s exploits usually end with either good footage or a good story; this one had both. “‘Let that madman in with his camera,’” he recalls officials in Washington saying.

Madman is an honorific here. Herzog’s best-known protagonists are coils of mad obsession and hubristic folly who usually end up in dire straits: Think Lope de Aguirre amid swarming monkeys in Aguirre, the Wrath of God, or Timothy Treadwell mauled by a bear in Grizzly Man. Their drive is rivaled only by the feats that brought their stories to the screen. In Fitzcarraldo, the character Brian Fitzgerald drags a steamship through the jungle, so Herzog did the same.

Now, at 81, the director is turning his lens on his most astonishing creation: himself. “It is not a biography,” Herzog says of his memoir. “It’s more in the landscapes, the poetry.”

It’s also a strange project for him. Herzog is hostile to introspection, writing at one point, “If you harshly light every last corner of a house, the house will be uninhabitable.” He also has a fluid relationship with facts. I ask him about “ecstatic truth” — the phrase he coined for narrative flourishes that claim to reveal deeper insights — and whether he has applied this philosophy to his life story. “I always give some question marks” to fuzzier memories, he says. (“I don’t think it was a dream, although it’s always a possibility,” he writes of one.) As for his choice of medium, Herzog, who has written several books, says, “People speak of me as a filmmaker, and I think you should first and foremost speak of me as a writer. There’s no one who writes like me.”

Indeed, his memoir is as singular as his films, rich with weird and indelible images (“The whole slope behind the house was suddenly alive with weasels”) and poetic ruminations (“Could I not break the spell that prevented her from dying?”). It is fueled by characters who are a little scary. When he was a kid, Herzog stabbed his brother during a fight. Decades later, the brother set Herzog’s shirt on fire at a dinner party. Both men found this “joke” hilarious, their violent rivalry echoing Herzog’s love-hate relationship with the star of Aguirre, Klaus Kinski, captured in the documentary My Best Fiend.

His friendship with Kinski is among many formative experiences Herzog details. Kinski terrorized the boarding-house where Werner lived as a child after moving to Munich from the Bavarian village of Sachrang with his mother and brother. “My mother,” he writes, “took the job of evicting” the mercurial actor after he locked himself in their communal bathroom for a day and a half and smashed it “to smithereens.” What makes the new book special in the Herzog canon is how it collapses time, such that disparate moments in history — from town criers to the internet, peasants’ scythes to robot farmers — collide on the highways of his mind. After the laboratory break-in, Herzog found footage shot by astronauts on the station that had launched Galileo. He charmed them into appearing in The Wild Blue Yonder by identifying which of them knew his way around an udder. “I wasn’t a creature of the film industry,” he writes, “just someone who at the end of the war had learned how to milk cows.”

I first encountered Herzog’s work when I got my wisdom teeth pulled as a teenager and binged some of his short documentaries — The Great Ecstasy of Woodcarver Steiner, The Dark Glow of the Mountains — while delirious on painkillers. When we meet, I embarrass myself by showing him a photo of us at a 2009 book signing. (“I remember the event,” he says. “Of course, I do not remember you.”) His distinguishing feature is his voice, a thickly accented monotone that lends a disarming matter-of-factness to his epic themes: the lunacy of men, the pitiless grandeur of nature. His voice-over style is influenced by hypnotism (the cast of his film Heart of Glass acted under hypnosis), but it sounds indistinguishable from his everyday speech. This blurring of person and persona has won him a second life online, where a Herzog parody account boasts tens of thousands of followers, and his performances in films like Jack Reacher and shows like The Mandalorian inspire delight and imitation. “I am a grateful victim of such satirists,” he writes, though he remains defiantly offline and doesn’t use a cell phone.

Herzog clarifies which aspects of his work are earnest and which tongue-in-cheek: He was being funny when he listed psychoanalysis as one reason “the 20th century was a mistake.” But he’s dead serious when he defends Hiroo Onoda, the protagonist of his 2021 novel, The Twilight World, as “not a madman.” (Onoda, a real-life Japanese soldier motivated by the fanatic worship of his country’s emperor-god, famously kept fighting World War II for decades after it ended.)

Herzog favors privacy, even as a memoirist. He has been married to his third wife for more than 25 years but admits to having few friends (“You could probably classify me as a loner”) and mostly avoids his fans. It’s an isolated existence that his book only partly illuminates. When I ask how he decided what to share and what to withhold, he responds cryptically: “It comes easily when you are a grown-up man — you know instantly.” Some things are appropriate for films or books, but others are simply life. “Let it stay life,” he says.

But life, abrupt and unfathomable, has a way of intruding on all his projects, whether they be fictions or not. Every Man for Himself and God Against All ends in the middle of a sentence — “it would be sought out by herds of deer, as though” — which I think is a typo until he corrects me. “You forgot the foreword,” Herzog says, instructing me to open my dog-eared copy to page two. “I was just working on the end of my book,” I read aloud as he watches me with an inscrutable expression. The memoirist describes a hummingbird hurtling toward him as he writes: “At that moment, I decided to lay down my pen.”